A Turning Point

Rat-a-tat-tat; rat-a-tat-tat, the Sten gun bucked in my hands as I saw the bullets strike home and the sand kicked up on the banking. “Bain!”, the corporal’s voice barked out behind me. Just as I began to turn he barked again, “Keep facing front, engage the safety catch and put down your weapon!”.

I was on the firing range at the Royal Army Pays Corps camp in Devizes, Wiltshire. I had arrived three weeks ago to begin my basic training as a short-term regular in the army; an alternative to doing my two years compulsory National Service. It was a pleasant early September day in 1953 and I had left school a few weeks earlier.

“Pick up your small pack at the barracks and report to the medical officer immediately, Bain” he said. “What’s it all about Corp?” I asked. “Damned if I know.”, he replied.

I handed him my Sten gun, returned to barracks to pack and made my way to the MO’s office. On checking in there I was told that they had found something on the x-rays which had been taken a week earlier, when a mobile unit came to the camp and anyone who had not had an x-ray during their signing-on process was to have one. “We are sending you to Tidworth to be checked over,” the MO said, “An ambulance is waiting outside”. (Tidworth was the hospital not far away.)

On arriving at Tidworth I was shown to a ward and ordered to strip and get into the bed provided, which I did, and laid there wondering what was happening to me but not overly concerned. After all I felt fit and well and was sure that I would soon be back in barracks. My main worry was that if it was more than a couple of days they might drop me from my current intake and all my mates and start me afresh with a new intake.

Eventually a medical officer arrived and explained that my x-ray had displayed some ‘shadows’ on my lungs and this could indicate some problems that they wished to investigate further. This was likely to involve further x-rays and some blood tests and they should have a clearer picture within a week. My heart sank at that since it would almost certainly mean I would be moved to a fresh intake.

The rest of my time at Tidworth was mostly uneventful other than undergoing several blood tests, answering many questions from medical staff, and having more x-rays. One incident I do remember with some embarrassment. One morning the nurse came to ask for my pyjamas (hospital issue) for laundering which I awkwardly provided by stripping under the bed covers. Off she went all sweetness and innocence, but without providing me with a clean set which she assured me would be distributed shortly. A few minutes later two nurses arrived to change my bed linen! I should explain that I was supposed to stay in bed, but that presented no problem to the nurses since they are skilled at changing bed clothes while the patient remains in the bed. My problem was that I had no pyjamas on and for an 18 year old lad confronted by two attractive young nurses that was not a situation to be relished; at least not in those circumstances. The crafty blighters had concocted the whole charade to embarrass me and check out my credentials! They eventually completed the process and went off smiling, no doubt to report the jape to their colleagues, and shortly after the first nurse returned with my clean pyjamas and a knowing smile. It was my first experience of the sense of humour of nurses, but it was not to be my last!

Towards the end of two weeks I had a visit from the medical officer with news of the findings from their various tests. I had pulmonary tuberculosis at a relatively advanced stage and I was to be transferred to the special military hospital at Hindhead, Surrey. But what about my basic training at Devizes and when would I be returning? “You can forget that laddie; your days in the army are over! Your personal belongings will be sent on from Devizes.” Suddenly the seriousness of the whole situation began to hit me: What about my plans to take my Customs and Excise exams at the end of my army term? What was I to do when I was discharged from the army? What were Mum and Dad going to think about all this and how could they visit me in Hindhead all the way from Great Yarmouth? How long was I going to be at Hindhead? My carefully plotted plans to become a Customs Officer had run into a serious problem, but it was not until later that I was to discover how serious.

Hindhead was going to be my home for the next few weeks and my treatment for tuberculosis began in earnest. It was a military hospital spread over a wide area in the form of low, single storey barrack-like buildings. The ward I was placed in had a mixture of soldiers with a variety of problems. Some had returned from the Korean War where they had seen tough action and suffered from nightmares as a result. It was not unusual to be woken in the night by a loud cry and, often, sobbing.

My treatment consisted of bed-rest and medication. The medicine was a combination of PAS and INH. One was a foul-tasting liquid and the other a large capsule which was very difficult to swallow. I had no idea what those initials stood for other than some chemical compound. I have since learned that INH is isozianid while PAS is para-aminosalicylic acid, but that makes me only a little wiser…

I also had to have a sputum mug by my bed and try to spit into it whenever I could so that they could test for infection. Once a week I also had a sample taken from my stomach which involved either swallowing, or passing via my nose, a thin rubber tube so that they could siphon out some of my gastric fluids. Not very pleasant but I soon learned the best technique to avoid gagging!

While I was at Hindhead the girl I had been going out with before I joined the army, and who wrote to me from time to time, decided there was not much future for our relationship and sent me a ‘Dear John’ letter. (That was what people called any letter that one received where the relationship was being ended). It came as no surprise and although it upset me at the time I couldn’t blame her. It wasn’t as if we had a long-term serious relationship.

My time at Hindhead was fairly uneventful but we had some funny experiences. We used to be given a bottle of stout or Guinness every evening as it was thought to provide iron in a palatable way! One old veteran in the ward used to horde his (against the rules) and also cadged any spare that others didn’t drink. Then at the week-end he would drink the lot and get thoroughly drunk and end up singing old songs and generally larking about.

I also had a real surprise when two old schoolmates turned up to visit, having hitch-hiked all the way from Great Yarmouth. It was really good to see them and to realise I had not been forgotten. Mum and Dad managed to get down a couple of times but it was not easy for them as they had to run the cafe that we had in Yarmouth.

You might wonder how we passed the time in bed 24 hours a day. It was at this time that I started my various handicraft hobbies. I did a bit of tapestry and also tried my hand at leatherwork. It passed the time and also produced a few things that were useful (a pair of kid driving gloves, for example).

By the end of November the powers that be decided that I should be transferred to somewhere closer to my home since I was never to return to army duty. So it was that early in December I was told that I would be moving to a civilian sanatorium at Kelling in North Norfolk. This was a hospital especially for patients with tuberculosis although they later started to take in patients with cancer if they were in need of chest surgery. Although Kelling was still quite a way from my home it was a lot nearer than Hindhead and my parents could get up and back within the day (there was a special coach that came at week-ends).

My transfer was quite a performance and I will take some time to describe it in more detail. On the due day I was wheeled out to a waiting ambulance and travelled up to Liverpool Street Station in London accompanied by TWO MILITARY POLICEMEN! I never knew whether they were there to make sure I didn’t run off or to protect me from the public — probably a bit of both.

When we arrived at the station I was wheeled along the platform and was shocked to see that a whole railway carriage (not just a compartment) was reserved for me and on every compartment were stickers proclaiming that the public were excluded and that ‘this person has an infectious disease’. They were taking no chances of some innocent passenger coming in contact with me!

The train duly set off on the journey and when we arrived at Norwich (where we would normally have to change to get a connection to Holt, the nearest station to Kelling) our whole carriage was disconnected from the train and shunted into a siding outside the platforms. By this time it was late afternoon and dark, it being nearly mid-winter. We sat in the compartment, my two MPs and me, and were getting colder and colder. There was no heating since we were not connected to any engine and this was a very cold winter evening. After at least an hour the MPs started to get restless and wondering what was happening since we had had no contact from anyone. One of them decided to get down from the carriage and walk up to the platforms to see if he could get some information. He eventually returned to inform us that the station staff had totally forgotten us and they were now hustling about arranging for us to be hooked up to the next train to Holt!

We finally continued our journey and after transferring to an ambulance at Holt we arrived at Kelling Sanatorium in the late evening. I was wheeled into a strange wooden building with open verandas on each side and split into small two-bedded cubicles. I got to bed and was given some warm food and a drink and told I would see the doctor in the morning and to get some sleep.

So began my stay at Kelling and the beginning of a totally different path to my life as a Customs Officer that I had envisaged when I joined the army six months earlier. Before I continue with that story I will go back to the early years to describe how I arrived at that choice of career in the first place.

Family Background & Early Years

My father was William John Bain, born in Poplar, East London in 1905 and my mother was Amelia Caroline (née Brown), born in Bow, East London in 1908. My granddad Walter Bain had been a stevedore (similar to a docker but actually loading on board the ship not on the dockside). He became unable to work due to arthritis just before I was born and Dad ‘inherited’ his stevedore’s ticket which was highly valued at the time. Nan, Hannah Bain (née Hall), was a lovely lady and used to have the family round for Sunday lunches and times like Christmas. I never knew Gran and Granddad Brown (my mum’s parents) because they had both died when my Mum was quite young — Gran when my Mum was only 8 (I think) and Granddad (who had been a cooper which is someone who makes barrels) when she was only about 14.

Dad had one sister, Ethel, and four brothers Walter Robert (Bob), Henry, Frederick and George. My Mum had three older brothers, Albert, George and Robert (Bob). So I had two Uncle Bobs and two Uncle Georges! Uncle Albert was a musician in the army and when he left he joined a dance band where he met his wife-to-be. They apparently went to work and live in the USA and I never saw either of them. The other uncles and aunts were a regular part of my life until I had left school, after which I would see them less often.

Dad’s brothers all lived and worked in London so I would get to see them while at my Nan’s house. In fact Uncles Henry and George never married and lived with Nan until she died. Aunt Ethel was the eldest of his siblings and married Osbert Old. They had two sons, Alfie and Eddie, and lived out at Dagenham or Becontree which is not far to the east of London in Essex. Next in line was Walter, known by his second name, Bob. He married Aunt Lizzie and had a large family of girls; Edith, Marjorie, Annie and Betty (all born by 1932) until the late arrival of his only son Robert in 1942.

Mum’s brother George was a sergeant in the Black Watch Regiment, but left the army when he married Aunt Ruby. She worked for a family who owned a furniture business. Uncle George joined their business in Newcastle and, in fact, their big store in the centre of Newcastle traded as G.M. Brown (my uncle’s name). They had a son Stuart who was a few years younger than me. Mum’s other brother Bob never married and was in the Royal Navy so was only around occasionally. He retired as a Chief Petty Officer just before the outbreak of war in 1939.

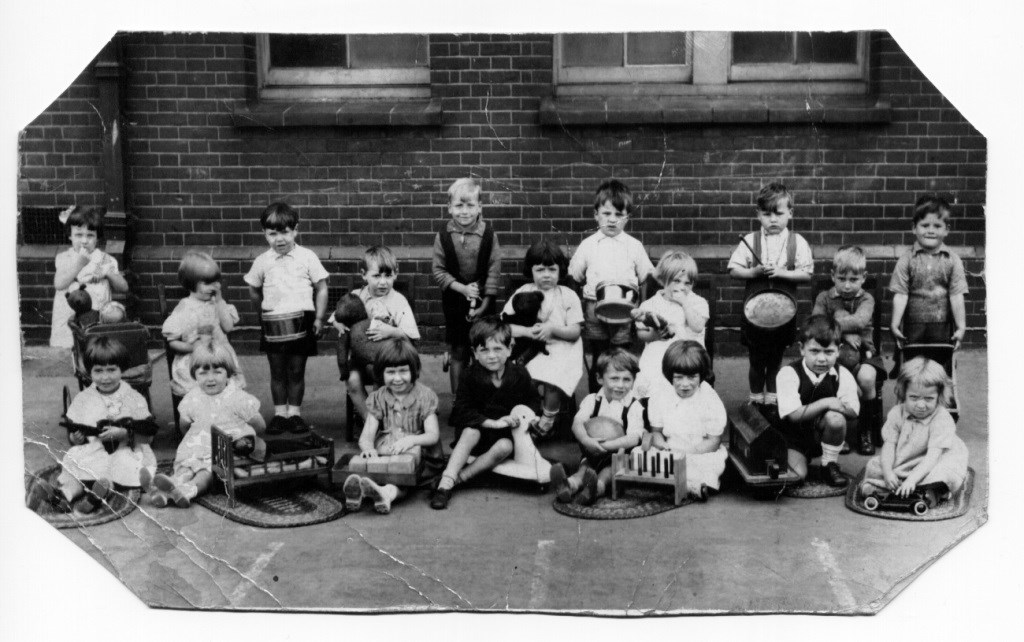

By the time I came along my parents were living in the same street in which Dad had been born and where Granddad and Nan still lived, namely Cotton Street, Poplar. I was born at number 19 on 13th February 1935 and within a month I was christened at All Saints Church, Poplar. I had an older brother Ronald (Ron) who was over 5 years older having been born on 13th October 1929. I have no memories of that time and soon after I was born we moved further east to Custom House because that was nearer the ‘Royal’ docks where Dad was to work. We lived in a small terraced house on Leyes Road and my earliest memories are of riding my little three-wheeler trike along the street with my friend Bertie (Bristow, I think). It was safe to be out on the streets then because there were very few cars and the fastest vehicle you were likely to see was the horse and cart!

I have only vague memories of other events before 1939. I have a memory of being held by my father and waving a flag as an important cortege drove by near to where we lived. I think it was a visit by the new King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (not the present Queen but her mother). More importantly I remember visiting Dad in hospital and seeing him with bandages and tubes sticking out of him. I should say some more about this period of my life, but as my memories are vague I am going to quote from my brother Ron’s own story of his memories of that time.

“My Nan and Granddad used to live just across the road from us at 24 Cotton St and Saturdays were always the day when all the relations gathered. That was also when we received our Saturday ‘penny’. Near where we lived in Cotton St was a road which on a Saturday would be lined with stalls selling all types of goods, yes a good old market; Chrisp Street was its name. Well, one day we were looking round the market — Mum, Bill and me — when it was noticed that Bill was no longer with us. Big panic, we searched for him high and low. Eventually we found him, there he was sitting on the kerb-side playing with his toy car and he didn’t even know he was lost. Big sigh of relief.

“My brother Bill wouldn’t have been very old when we moved to Abbott Rd, but my memory of this period is very dim. I should mention that whilst we lived at Poplar my father had an extra part-time job working at a theatre called the Queen’s. I remember he used to wear a crimson uniform. As a result of this we used to get free tickets to various shows and saw all sorts of acts on the stage, and of course at Christmas times our Nan would take us up the ‘West End’ to see the pantomime. I reckon Bill was about 2½ years old and I would have been about 7½ when we moved to 74 Leyes Rd, Custom House. I attended Prince Regent Lane Junior School which was just at the end of our road. I can clearly remember one boy’s name was Peter Amos because he was first on the register and I was second. We had 4 school teams: Nelson, Drake, Clive and Wellington. I was in Wellington which was blue, and blue has always been my favourite colour ever since.” (I later went to the same school, and perhaps I was in Wellington because blue is also my favourite colour).

“My father was a stevedore and worked on the docks which were nearby. I think it was around Christmas 1938 that my father became seriously ill with double pneumonia and an abscess on the lung. He was rushed to Whipps Cross Hospital. Two things stick in my mind at this time. Firstly, the children in the street were trying to convince my brother that there was no Father Christmas and that it was my dad. It couldn’t be, Bill argued, because he had received all these Christmas presents and yet our dad was ill in hospital. There rests his case.

“Before I mention the second incident I ought to tell you that my mother’s brother, Uncle Bob, was in the Royal Navy as a Chief Petty Officer at this time. Mind you, as a little boy when I used to see him in his uniform I used to think he was nothing short of ‘Admiral’. Anyway, what happened was Uncle Bob sent us a great big Christmas hamper. It had everything in it that you would ever want for Christmas. What I couldn’t understand was that with all these wonderful things my mother was in tears. ‘Why are you crying Mum?’ says I. And of course it was because our Dad wasn’t there to share all the goodies. Anyway Mum gathered up all the perishables that we could carry and off we went on the bus to Nan’s house. There was some wonder pill called M&B tablets and it was these that helped my father make a good recovery. (I vaguely remember the arrival of this hamper).

“To the rear of our house were allotments and then there was this little river called River Connaught, which had a path down one side and a grassy strip on the other side. We would ask our parents to pack us up some food and also raw potatoes and we would all set off to this river and set up camp. We would get a camp fire going and cook our potatoes in the embers. There was no such thing as tin foil so the potatoes went straight in, but they would taste delicious even if they were eaten half cooked sometimes. Having set off on our camping expedition at about 9.30 in the morning, by the time it got to 1.00 pm we would be off ready for home having eaten all our food and asking our mothers if it was time for dinner.

“Another adventure, if you could call it that, was to go fishing for tiddlers. These were either sticklebacks or red throats, both about 1” to 2” long (2-5cm). When you were lucky enough to catch a fish you put it in a jam jar.

“Further excitement could be had by either walking, or better still, catching a train to Woolwich. I remember a time when I was at some railway platform and, as all us lads used to do, I tried the chocolate machines to see if by some fluke a bar of chocolate would come out. Well, on this occasion I tried the machine as usual and lo and behold it coughed up a bar of chocolate. I kept trying it and ended up with about six bars of Cadbury’s Chocolate. Having arrived at Woolwich the idea was to go on the ‘free’ ferry across the River Thames to the south side and to return via the foot tunnel. We would do this as many times as we could until one of the men on the ship would notice that we had been on a few times. In fact there were two ferries plying back and forth all day long, so we would get a good run for our ‘money’. Did I say money? It didn’t cost us a penny. Whilst we were on the south side of the river Thames we would sometimes go to Abbey Woods or it might have been Bostall Woods and at the right time of year, pick blue bells and sell them for 1d (one old penny) a bunch. Such enterprise!

“Near where we lived was the trolley bus terminus and it was possible, especially during school holidays to get a sixpenny (6d) ‘all-day-ticket’. Like it says, with this ticket you could go anywhere you liked on any trolley bus. I also used to like going, as a family, to our local speedway and watch these motor cycles racing round the track. Our team was West Ham, ‘The Hammers’. Of course, as children we used to copy them on our bikes. Near where I lived was an unmade road and this became our dirt track. Four times round the circuit (anti-clockwise) skidding into the bends. My bike was a small one with 22” wheels but I could go round like a bomb. (This reminds me that I used to race my friend Bertie on our trikes; I was ‘Bluey’ Wilkinson and he was ‘Tiger’ Stephenson, who both rode for the Hammers.)

“I used to see my cousins on various occasions throughout the year, but always the most vivid memories were at Christmas time. The usual system would be for us to open all our Christmas presents at home and then select our favourite, or ones that would travel easy, and on Christmas morning off we went to Nan’s, which was about 5 miles away on a bus. There we would all gather for the festivities. It would be the rare occasion when the ‘front room’ was opened up and we would play at all sorts of games and, of course, enjoy all the food.

“There was one particular thing we used to have called ‘snap dragon’. Lots of raisins would be put on a large heatproof plate with hot brandy poured over them and then with all the lights out this plate would be ‘flamed’ and everybody had to make a ‘snap’ at the flaming raisins whilst the brandy was still lit.

“When we used to go on holiday to Laindon and/or Bognor Regis I remember I had some second cousins on my granny’s side of the family. It was one of these cousins who asked me to smell this mint that he was holding up to me and it stung my nose because it was a stinging nettle. That’s how green I was about country life.

“I remember an old lady called Great Aunt Polly (I suppose it was my granny’s sister or something) and she lived in a lovely thatched cottage at Bognor Regis. It had a lovely long garden at the back going right down to some railway lines and I can just see it now walking down the garden path and it was here that I had my first taste of greengages. The cottage itself was next door to a country type pub with some name like the Royal Oak. I remember the cottage and pub used to appear together on one of the local postcard scenes.

“All these events happened as part of my life with no special dates to really register the passing of time, until June 1939. These are the events as I remember them. My father, as I’ve mentioned, was a stevedore working on the docks and on this particular day whilst he was working he fell down the ship’s hold. This was a drop of about 35ft (10m) and although there should have been a safety net, on this occasion there wasn’t. However, so far down there was some staging, which they say helped to break his fall and thus saved his life. He received a fractured jaw, broken wrist in about 5 places and also other injuries. He was rushed to our nearby local accident hospital, my mother was informed and my brother and I were looked after by friendly neighbours. Of course I didn’t know about all this at the time, only that dad had had an accident. I remember my brother Bill and me going to see him about a week later when he’d been patched up and my dad asked us to give him a kiss. Well my brother did, but I’m afraid I just couldn’t face up to it and refused. His face was all battered and bruised, his lips all swollen and cracked and some horrible metal straps that were keeping his jaw in place. Maybe it was because I was at a sensitive age but I just couldn’t do it. He started to make a slow recovery and then was transferred to Whipps Cross Hospital and because he had been to this hospital before he suddenly realised where he was and his memory started to return, because before all was somewhat vague in his mind.

“Meanwhile some crafty solicitors, representing the ship’s owners I believe, came along and got my mother to sign on my dad’s behalf some papers which they say would entitle her to ‘workman’s compensation’, otherwise she will get no money. This meant dad would receive about £3 per week or thereabouts, but what they didn’t say was that we gave up the right to sue them, or so I was told in later years. Well, as I said, Dad gradually got better and came out of hospital and in late August we went on a late holiday to some relations’ cottage in Laindon where we had had holidays in the past. We had only been there a few days when all sorts of news started to come on over the radio. We had to pack up and do a quick flip back to London. Yes, that’s right, the Second World War was about to start.

“My father and mother explained to us as best they could what it had been like for them in the First World War 1914-18 when they were only children living in London with the old Zeppelins flying over. They said it would be far better for us if we were evacuated to the country where we would be safe, and so in September 1939 Bill (4 years, 6 months) and I (9years, 11 months) were evacuated to Bridgwater, Somerset.”

And so a whole new chapter in my life was to begin as Ron and I were sent away as evacuees.

Orders to begin the official Government Evacuation Scheme were issued at 11.17am on 31st August 1939, and the first evacuees left London the next morning. In the next four days, 376,652 schoolchildren and 275,895 younger children with their mothers left the capital for areas of greater safety. (Source: The Telegraph)

The War and Evacuation

I have to confess that my memories of the events of our evacuation are hazy. I can remember travelling with a lot of other children on a train and arriving very tired at some school hall. Also some incidents during our time at Bridgwater, but I am going to refer to Ron’s story once again to fill in the background to that period at the beginning of the war.

“War was declared on September 3rd 1939, but even before that date there were all sorts of activities going on all around, which gave one a small clue as to what was happening. Air-raid shelters were frantically being built. Anderson shelters were constructed in most people’s gardens. Everyone was issued with gas masks and gas indicators were to be seen outside police stations and public buildings.

“Anyway off go my brother and I with our gas masks and luggage of sorts and labels hanging round our necks along with loads of other children, plus a few adults to the railway station. I think it was Paddington Station (as seen on Monopoly). We had said farewell to our parents with a promise to write home as soon as we could. No one had a clue as to where we were going and if anyone did, they certainly didn’t tell us. I seem to recall we were given some food somewhere along the way and finally after a very long day we arrived at this school in this town, still not knowing where we were. Names were called out and children would be meeting their new foster parents. Ours turned out to be a Mr and Mrs Thorne of 32 Bristol Rd, Bridgwater, Somerset.

“Firstly a little bit about Bridgwater, about 120 miles from London, 30 miles from Bristol and a similar distance from Bath. It is situated on the river Parrot, which has a ‘bore’ similar, but not as famous, as that of the river Severn. Admiral Blake was a famous son and his gardens are now open to the public as a park. The Duke of Monmouth is featured somewhere around about and there was a famous battle fought nearby called the Battle of Sedgemoor. So ends the history lesson.

“When we were all settled in, possibly after a day or so, we had to report back to the school and allocated different classes. The evacuees were kept separate from the local children and we also had our own teachers. We gradually all settled down to life as evacuees and were accepted by the locals. I wrote home to my mum and dad fairly regularly, about once a week.

“Mr Thorne worked for the local shirt factory. He had been in the 1914-18 war and had lost the tip off one of his thumbs. Mrs Thorne (‘call me Aunty’) kept house and she had long black hair, but I never saw it like that because she always had it tied up in a tight bun; they would be maybe 45-50 years old. There was a son called Kenneth who was 18 and worked for ‘Boots’ in the town, as a chemist. There was also a lodger who came on the scene somewhere along the way, and he was called Jack and was about 22. That sort of sets the scene for the household. Bill and I slept in a double bed in a room of our own. This was one area where we had a problem because poor Bill (don’t forget he’s only 4½) used to wet the bed, and every time this happened Bill was punished — no supper, certainly not anything to drink and other sorts of mental anguish. It got to a state where Bill would wake me up in the middle of the night and tell me that he’d wet the bed, and we would be frantically shaking the sheet up and down in an attempt to dry it out. Christmas came and went and I’m not sure when but we were issued with identity cards (my number was WOAL 167/5) and of course ration books. I can’t remember really what the rations were, also at this time we started ‘school dinners’.

“Life continued on apace; I was still in the cubs and I was a server at the church, I used to also have to take my turn at pumping air into the church organ. The reward for this was to be able to pick a pear from the vicarage grounds. We used to belong to the Odeon Junior Film Club and go to the pictures on Saturday mornings.

“We formed a ‘gang’ and to be a member one had to eat a cube of horseradish (about the size of an Oxo stock cube). We used to dig it up and cut the cube from the roots. I know it sounds daft now, doesn’t it! There also were some old disused brick ponds, and we used to make rafts and try to sail them. (Very dangerous I realise now). We were always told to be in house by a certain time and this was sometimes very difficult for us. We would ask a casual passer-by, (very few and far between) “Could you tell us the time please, Mister”. What! Big panic frantically trying to get all the muddy clay off our shoes, finally wiping them over with wet grass so they looked nice and shiny and then running home for all we were worth. Of course when we got home ‘Aunty’ would say, “Where have you been? Just look at your shoes.” We would look down at them and of course by now our lovely wet, shiny shoes had dried mud all over. “No supper for you tonight my lads,” and so off we were packed to bed. Now, I must tell you this, when we left London Mum told me that I was to look after my brother and make sure he was a good boy, he was told to do what his big brother told him or else. Having told you this you will understand this next bit I’m about to narrate. Here we were walking down the main street in Bridgwater and Bill did something wrong. I can’t remember what it was now, but as a result I smacked him. Well he started to cry and even tried to hit me back. (I remember I used to try to kick him on the shins!) Suddenly this woman comes up who had seen what was going on and said to me, “Leave him alone you big bully. You’re twice his size”. Where-upon to her amazement Bill turned to her and said, “He’s my brother and he can hit me when I’m naughty, so there”, or something like that. The woman just didn’t know what to say. That’s what I call brotherly love. I’ll never forget that.

“Meanwhile back in London my dad started to have epileptic fits as an after-effect of his accident. I didn’t know about this at the time because they didn’t want us to worry. They would occur about once a month, but without any warning and the doctor said they could get worse or better. No one could say. He had to take phenobarbitone tablets to help him. I wouldn’t like to put any dates to this period, but the bombing had now started in London. Whether it was before or after Dunkirk I don’t know, but because of these troubles and my father’s health the doctor thought it best if he was evacuated, so he and mum went off to a place called Hemel Hempstead which is near Watford in Hertfordshire.

“As I said earlier the River Parrot had a ‘bore’ tide. This was quite a sight to see. The times of the tide were written on the notice board on the bridge in the main street. People used to stand on the bridge and watch it. ‘What on earth was it?’ you say. Well, one minute the flow of the water would be going along all nice and calm in one direction and the next minute this huge wave used to come along and completely change the direction of the flow. Apparently it used to catch quite a few animals by surprise and you often saw a dead sheep or two following in the wake of the bore.

“I reckon it would be about Easter of 1941 when my Mum and Dad, or maybe it was just Dad, came to see us on a special coach trip and for the first time we told him how unhappy we were. And so what happened, he made some feeble excuses to aunty about his health etc., and took Bill back with him to Hemel Hempstead with a promise that he would make arrangements for me to go to a special boarding school nearby where my parents were staying. Within a very short space of time, although it seemed like an age then, I was packed up and on my way to another adventure. Mind you, before I’d even left Mrs Thorne had got herself another lodger.”

I have a few memories of Bridgwater and of course I remember the problems I had with bed-wetting. Mrs Thorne used to rub the sheet in my face and rant at me. I remember being very thirsty at bedtime, but never being allowed a drink. However, there were some happier memories too when we were out at play. I can remember the Saturday morning cinema and the excitement of the cowboy films and a science fiction character called Flash Gordon. I remember seeing the Parrot bore and playing around the clay pits. There was always a terrible smell in the air around Bridgwater and this was because of fumes from the Cellophane factory. I have a memory of my first sweetheart! She was a girl who lived just along the road from us and I would walk to school with her and always tried to sit next to her in class.

I also have a memory of an incident near the river when we were playing on a jetty. Sometimes kids would pretend to push you off but catch your clothes at the same time so you never really fell but got a fright. On this occasion I was pushed, but the lad failed to get hold of me and I actually fell! Luckily the tide was out and I fell down onto the muddy shore. Ron came to rescue me and hauled me out, but I was in a real mess. I know we got into trouble when we finally got home. (Perhaps it was the same incident with the shoes that Ron describes above?)

Anyway as Ron describes, our Dad finally came to rescue us and I was taken back to live with Mum and Dad in our new home in Hemel Hempstead.

Hemel Hempstead & Boxmoor

Our home in Hemel was in a fairly large house converted into flats and I think ours was on the 1st floor. I remember it was just along the road from the school I attended and nearby was a sort of canal in which there were cress beds. (Watercress is very popular as a salad green and grows like a pond weed; Hemel was a famous growing area.) There were other children living in the house and we used to play together quite a lot.

Mum was going out to work and Dad was still too handicapped to work properly. We did not have a lot of money but my Dad did have ‘A Magician’ who sometimes left me treats. I should explain this although I was convinced it was all true at the time. Sometimes Dad might have some spare money and would buy me a treat (a small toy or sweets if he could get some). Quite cleverly he or Mum would guide the conversation round to the subject and I would express the wish to have such and such. Dad would look serious and say well he would have to have a word with his Magician and would pretend to go into a sort of trance. Then he might say the Magician had found what I wanted but it was somewhere in the room and I had to find it. I would start looking with the Magician telling me (through Dad) if I was ‘Hot’ (close to it) or ‘Cold’ (nowhere near it). Eventually I would discover the surprise and be amazed that the Magician could not only know what I had wanted, but had been able to conjure it into the room!

Ron never came to live with us at the house in Hemel but, instead, came to stay in a sort of boarding school nearby at Boxmoor. Let me hand back to Ron to describe this event for you.

Pixie Hill Camp, Boxmoor

‘Well, let me first of all give you a bit of background. Pixie Hill was built just before the war. It was a sort of holiday camp school for boys and its purpose was to give holidays for poor children of London who could not otherwise afford one. Unfortunately it was never used as such. Instead a whole school called Tollgate School, Plaistow, complete with teachers was evacuated there. My father had been very fortunate in finding me a place here. My luck was further in because my best pal from Leyes Rd, who I hadn’t seen for ages, was also there and I ended up in the same dormitory as him. His name was Brian Sellers, he was about a year, maybe 18 months older than me and he was the first boy I met when I moved to Leyes Rd. He left the area about 1938 when his mother divorced and left to live elsewhere. So it was great meeting up with him again and I soon settled in to my new life.

The school was completely self-contained, even having its own hospital. We never used to have any normal type holidays, because we couldn’t go home or anywhere if we did. Instead the headmaster at assembly would say, “It’s a fine day so I don’t want to see anyone in the classrooms”. Sometimes we used to be allocated jobs to go and help the local farmers. It could be fruit picking, helping with the wheat harvest or even (worst job) potato picking. We never used to get paid for these tasks as individuals, but instead the farmers would make a donation to the school fund. Eventually the headmaster bought for us a gigantic electric train set. Each dormitory could borrow it and on a weekend it went into one of the classrooms for anyone to use it, but under supervision. Each dormitory (5) was named after each continent (I think) and could accommodate about 40 or so boys with accommodation at each end for a teacher and a store room. So at a rough guess there were about 200 to 250 lads at Pixie Hill.’

This school was not far from us and we used to see Ron occasionally. He mentions in his story about putting on the school panto and I can remember going to see a show there. I can remember the show had a lovely song in it sung by a boy (but I think dressed as a girl) with a most beautiful voice. The song was ‘Lover Come Back to Me’ and it still brings back memories when I hear it. I can also remember having some refreshments in a dining hall, including a cup of tea. Unfortunately with rationing there was no sugar, but I spotted a jar with some in (or so I thought) and happily added some to my drink. It tasted foul! It wasn’t sugar, but salt! (Many years later I visited friends in Hemel and sought out the cress beds and Boxmoor).

We were in Hemel for about a year and out of the blue we were heading back to London and Leyes Road. The war was still raging, but the worst of the blitz on dockland seemed to have eased and Mum and Dad decided we could risk returning. So another new turn in my life and we were to be reunited as a family after 2½ years.

Back in London

Leyes Road Again

When we returned to London things had changed and my memories are stronger. The road was only just recognisable, as the whole of the Prince Regent Lane end was a bomb site. The school we had attended was just a pile of rubble. Luckily for us our end of the road was still intact.

Our house at number 74 was a terrace with a front room off a hall passage where the best chairs were kept and even an old upright piano. The passage led to the living room which had an old-fashioned black cast iron range, a dining table and chairs and a couple of easy chairs. Stairs led from here up to the two bedrooms with a coal firegrate in each. Through the back was a scullery that had a cooker and a fired copper boiler built into one corner. Alongside was what looked like a work surface, but when that was lifted there was a bath. The fire was lit under the copper boiler to provide the hot water for the weekly laundry and the weekly baths! Outside, attached to the scullery, there was a toilet and a coal house/store. There was quite a long garden where Mum used to grow pinks and carnations, her favourite flowers, but dominating it now was the Anderson shelter. This was built by digging a large pit and lining it with corrugated iron sheets curved at the top so as to meet and bolt together. Then the earth was heaped back all around it and over it so that it just looked like a mound of earth and grass. A couple of steps were cut at one end down to a small entry door. Inside on each side there was a low bunk bed and a few shelves. This was to be our refuge during air-raids which were still occurring though with less frequency than in 1940/41. (By 1941 Britain had won the Battle of Britain, stopping the massive air-raids which had been hitting the country until then. After that the Germans found it more difficult to mount raids, especially during the day, with such force and the air defences were coping much better.)

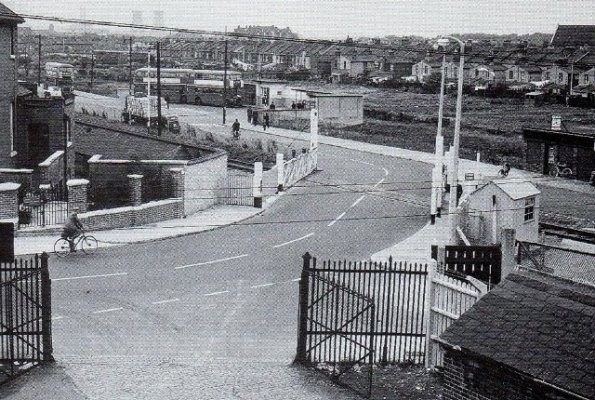

Beyond the garden was an area containing allotments where people had plots of land for growing their own vegetables and beyond that the river/canal called the Connaught. Past that was Victoria Dock Road which led into the docks and the trolley bus terminus.

Ron and I started back at school in Shipman Road, just the other side of Prince Regent Lane and so within easy walking distance. Because Dad was still unfit for work it was Mum who went out to work every day, while Dad stayed home to look after us and the house. He must have got very bored with his life, but luckily for us he did not drink alcohol so at least didn’t turn to that to relieve the boredom. What he did love to do was play Whist and he would go to Whist Drives where he often won small cash prizes. (A Whist Drive is where a number of people gather together to play the game. They are divided into tables of four and after each hand two of them move on to the next table. After all the hands have been played and everyone has played everyone else, the tricks scored by each person are added up and those with the best scores share the prize money which comes from all the entry fees they have paid.)

Mum worked at the railway yards in Stratford, not far on the trolley bus, cleaning the engines and carriages. It was a hard life for her, but we kids were never really aware of these things. Our lives were a long round of school and play.

I don’t remember much detail about school. I remember we had milk issued every day (a small 1/3 pint bottle with a cardboard disc as a lid in which you pushed out a smaller hole to stick in a straw.) We used to collect the lids to play a game with cigarette cards. These were so named because these small cards came in each pack of cigarettes and we used to collect them a bit like nowadays people collect Doctor Who or MatchAttax cards. They came as sets with different subjects; cricketers, footballers, flowers and all sorts of other subjects. On the front would be the picture and on the back information about it. We never often collected a full set, but were just interested in getting as many cards as we could. We would play each other to win them and this is where the bottle tops came in. One way of playing was to prop a row of cards against the wall (each person putting in the same number) and then you would crouch some way away, usually the other side of the pavement, and flick a bottle top at the cards. Any that you knocked down you kept. Another way was to just flick a card ahead of you each in turn. If you managed to land your card overlapping another card or cards you picked them up to keep.

Another memory of school was that we did not always stay in for school dinners. Sometimes I would take my sixpence (2½ p nowadays) and go to the Pie & Mash shop. These were a tradition in London and were cafés where you could buy these mince pies served with a big dollop of mashed potato and covered in ‘liquor’, a sort of thick green gravy!! They also sold stewed and jellied eels. Mum and Dad loved these but it was a long time before I got the taste for them. What I do remember is that these shops also often sold the live eels which you could take home to cook yourself. Mum sometimes did this but they are very slimy and slippery to hold when you were trying to cut off their heads and gut them! It was usually better to get the shop to do that bit since they were well practiced at it. A few years later I used to love watching them down the market because they were so quick at it. Most of my other memories of living at Leyes Road were about our playing out!

The bomb site at the end of our road was a great playground. One of the things we did was to look for pieces of roof slate and then carefully chip away at it to form the shape of a gun. These were our toys for playing Cowboys and Indians or for fighting the Germans! We also explored the ruined houses and buildings to look for any ‘valuables’ that might have been left lying about. I remember we once found a pile of plastic discs in the ruins of an old shop and thought they were valuable ivory. I think they were just counters from a set of Tiddlywinks or something like that.

We all had catapults which we made by finding the right shaped branches from a tree and attaching ¼ inch rubber elastic to it. We became good shots and used to practice firing at old bottles and jars. A favourite target was to throw an old light bulb into the Connaught behind our house and then see who was first to hit and sink it. All this would be considered naughty these days and I would not encourage small children to try these things now. But it was good fun!! The river did give us the opportunity to fish for ‘tiddlers’ or sticklebacks (small fish about 2 inches long) and we would keep them in a jam jar with a piece of string tied round the neck to form a carrying handle. Just the way Ron described earlier, as he and his mates did before the war when he was my age.

Having a big brother was useful and Ron taught me all sorts of things, including how to roller skate. He was very good at it, but it did not take me long to be capable of staying on my feet most of the time. Because there was very little motor traffic around our street it was OK to just skate along the road; something you could not do now very safely. Some motor traffic went along Victoria Dock Road and I can remember hanging on the back of them and being towed along on our skates. Again very dangerous and not to be recommended… In fact if our Mum knew about it we would have been in for a smacking. Not that our parents hit us much, but if Mum got cross and upset she would sometimes give us a smack around the ear. Not very hard but we used to shout out, “Not with your ring hand, Mum.” This was because she had quite a heavy gold wedding ring on her left hand and even with a gentle slap it could hurt!

Most deliveries were still done by horse and cart although some of the milkmen had electric trolleys which would come rattling along the road. I sometimes used to help our milkman on his rounds by going along with him and dashing back and forth with the milk from the cart to the front doors. He would give me a few coppers at the end and I would buy some sweets or a treat if I could find a shop that had any in. That may sound strange but sweets, along with most things, were rationed and even if you still had some coupons left in your ration book it was difficult to find anywhere that had the supplies. News would flash round the neighbourhood if some shop got some delivery and there would be a mad rush to get there before everything was gone and you often had to queue and hope there was still some left when it was your turn.

Most of our play was in the streets or on the bomb sites and when we were not at school we would be out and about. The girls would have skipping games or swinging on a rope tied to a lamp post. Boys sometimes joined in these games, but usually we had our own games. Football, cricket, marbles and playing with cigarette cards as I have described, were all favourites. We also played with spinning tops which were shaped a bit like a mushroom and you kept it spinning on the ground by whipping it with a leather lace tied to a stick. A hoop and stick was another popular game. The hoop was usually an old bicycle wheel rim and you bowled it along and ran alongside it keeping it upright and moving with a stick or piece of iron.

The boys tended to form into gangs and go around together and although we got into mischief and even had fights with rival gangs they were not like today. At most we would have stone throwing battles and raid each other’s ‘dens’, which were usually makeshift shelters built from old boards and corrugated sheeting that would be lying about the bomb sites. Even within a gang there would be disputes and fights to see who was boss. A fight could either be with fists or wrestling and it never usually went too far before a winner would be declared. I never liked fighting with fists but I was good at wrestling so was able to hold my position in the gang. Another way of establishing the ‘pecking order’ in the gang was through your deeds of ‘derring-do’. This could involve climbing a particular obstacle or being prepared to jump down from a spot higher than anyone else; perhaps even proving to be a better shot with the catapult.

The war was still going on, but for us kids the main effect was through rationing of our sweets and goodies and the air-raids. As I said these were less frequent during the daytime but were still quite common at night. Because we lived near the docks these were a target for the German bombers, and so we had to take precautions. If the raid was during the day we had to go into the nearest public air-raid shelter. These could be a reinforced concrete building especially built, or sometimes a basement of a building or down in the underground railway stations. At night it meant getting out of the house quickly and into the Anderson shelter in our garden. We would sit there with a small paraffin lamp or a torch and listen to the drone of the bombers and the crump of the bombs falling. A siren would sound when the bombers were coming and it would sound again when they had gone. Once the ‘All Clear’ siren went we would come out of the shelters and look around to see what damage had been done in our area. We were lucky that none fell too close to us while we were in Leyes Road but in nearby streets we would see the effects of the bombs on the houses and hear about who had been killed or who had miraculously escaped. As kids we didn’t really take in the horror of all that and, in fact, thought it an adventure to explore recent bomb sites to look for pieces of shrapnel (bits of bomb shell or casing). Ron once found a whole incendiary bomb shell which was his pride and joy as a war trophy.

As part of the air defences there were ‘ack-ack’ sites (areas where anti-aircraft guns were placed) and there was one quite near us where we would go to look through the fencing at the soldiers tending their guns. Another defence was the raising of balloons high up into the sky. What good would a balloon do you might ask. Well these were huge balloons like the big blimps you see hovering over sports events nowadays and they were tethered by long steel cables which could be winched up and down. Because they went very high up into the sky they could stop the dive bombers coming too low to make it easier for them to hit their target. You see there were two types of bombing raid. One was by big bombers high up that dropped high explosive bombs or bunches of incendiary bombs (smaller bombs that burst into flame and could cause widespread fires). Because they had to drop these bombs from a height it was not always easy to be accurate. The other type was by dive bombers, slightly smaller but faster and more manoeuvrable, which would drop low over the target and drop their bombs as they were approaching their target. These were a bit more accurate and you may see film of this type of bombing when the planes attacked a particular object like a ship or road convoy. They might also come in firing their machine guns as well so you see it was important to stop them flying too low. That is what the barrage balloons, as they were called, were for. Not so much the actual balloon, although I don’t suppose it would do a plane much good to fly into one, but the cable that the balloon kept up. It would be very difficult for a plane to fly in and keep dodging a network of vertical cables suspended in the air which could not easily be seen.

At night during a raid the sky was spectacular around our area. The guns would be firing, but to help them see their target they had huge searchlights that shone into the sky to try to pick out the planes in their beam. The light beams would be swinging this way and that across the sky like a giant laser display that you see nowadays at concerts and things. To us kids it was all a show but to the adults it was in deadly earnest.

Because we were near the docks we would often go over to the dock exits in the hope of catching the arrival of a boat from America. Why? You might ask. Well the US sailors did not have rationing like us and we would hover around the gates as they came out for some shore leave and try to cadge sweets or chewing gum from them! “Got any gum, chum” was a common catchphrase used to address the Yanks, as the Americans were called. If we struck lucky it was considered a great coup and we would dash off to share our spoils. The chewing gum they had was the long strip type and at that time it was not available in Britain. Our chewing gum was the small, sugar coated, type. We also had bubble gum which was fun when you could get it! We would have competitions to see who could blow the biggest bubble.

So life went on around Leyes Road for a year or so. Dad still suffered from his fits and these were always a bit frightening although gradually he was able to tell when one was coming and could prepare himself and us. You see a fit involved him collapsing on the floor and writhing around for some time until he just seemed to lie unconscious. After a time he would regain consciousness. He usually had a terrible headache, and would have to rest for a while. At that time it was thought best to try to get something between his teeth for him to bite on because during his fit his mouth would clamp tight shut and if his tongue happened to get in the way he could give himself a nasty bite or even bite the end of his tongue right off! We children learned how to cope with this and could take the appropriate action, but I remember being out with him on one occasion when a fit came on. I stayed relatively calm and tried to do what I was supposed to but the people around panicked a bit and tried to get me out of the way and call for an ambulance. By the time the ambulance arrived the worst of the fit was over and after a rest we were able to carry on and make our way home. The adults couldn’t believe that a small 7-8 year old boy would know what was needed.

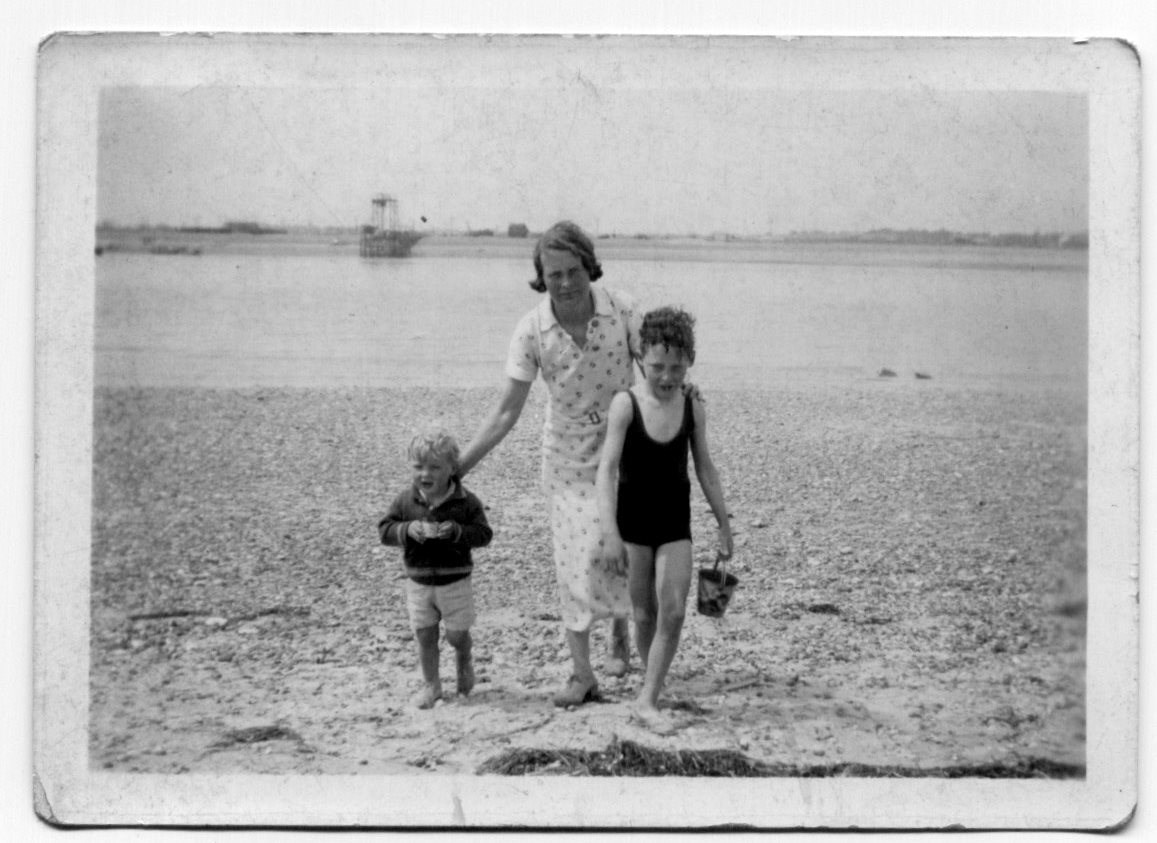

Family holidays were rare at this time but we did occasionally get away as far as Laindon or Southend. Nan had some relative with a sort of holiday chalet at Laindon and it was great to be out in the country. Dad loved to go picking blackberries or nuts and it was great fun foraging in the woods after being on the streets and bombsites. We also went down to a Great Aunt Polly in Bognor Regis (a seaside town on the South coast of England). She had a huge garden with an orchard and we were allowed to pick our own apples and pears. This was a rare treat for us and I guess we might have overdone it a bit and ended up with tummy aches!

Of course throughout this time there were regular visits to Nan’s house and sometimes if I was in a bit of trouble at home I would run away to Nan. This would involve me telling Mum or Dad that I was running away and they would say “OK then, you had better pack your bag and go.” Then they would pack this very small brown suitcase with my pyjamas and underclothes, give me sixpence and send me off! I would walk round to the trolleybus terminus to catch the bus to Forest Gate, change onto another bus and arrive in Poplar and my Nan’s house. After a day or so Nan would reverse the process and off I would trot back home or perhaps the family would come over for their regular visit. Remember there were no mobile phones and such and we never even had an ordinary phone so my parents must have had great trust in my being safe and able to do the journey. In fact until she died, running off to Nan’s was a regular haven for me and I loved visiting her. We would go off on trips into the West End (of London) and go to the theatre or have tea in a Lyons Corner House or just go to the local variety theatre. Ron mentioned about Dad working at the theatre in Poplar and getting free tickets. Well at this time it was Uncle Henry who worked there and we were able to go along almost anytime and climb the stairs to the Upper Balcony box office (which was separate from the main one). The lady there was a friend of Uncle Henry and if there were seats available she would just let us in. I remember seeing quite a few of the famous music hall artists of the day. Ted Ray was one and Max Miller was another that I remember.

I would also sit with my Granddad and play cards or dominoes with him. He taught me to play Cribbage which has been a favourite card game throughout my life. I mentioned that Granddad had bad arthritis but I think it may have been something a bit more serious. All I remember was that his legs were crossed in front of each other and he had to shuffle along with the aid of his walking sticks. This meant that he spent a lot of time just sitting so he was glad of someone to sit with and play cards.

Around the middle of 1943 Mum and Dad announced that we were once more on the move. Apparently the lawyers had been in touch with my Dad and instead of him getting a small weekly payment as compensation for his accident they would pay him one lump sum. I never knew how much, though Ron seems to remember it was £1500; not a lot today but it was enough then for Mum and Dad to decide to buy a restaurant business. They went into partnership with friends called Harry and Daisie Marshall and bought a business in Wandsworth, south-west London, called The Rendezvous Restaurant. It was a big house at 16 Bellevue Road, right opposite Wandsworth Common and was big enough for both our families to live in. The Marshalls had three daughters around the same ages as Ron and me. So began another phase of my life in another home!

The Rendezvous, Wandsworth

Living at the Rendezvous was a real luxury compared to all our other homes. For a start there were indoor toilets and bathrooms. No more creeping outside in the dark with a torch to go to the toilet. Hot running water for a bath! Another great benefit was lots of food available. Although rationing still applied to a café or restaurant your allowance depended upon the returns you made to the authorities about your turnover and the number of meals you served each month. I think our own meals could be included in that, but at any rate it meant that there was usually butter and eggs available and plenty of meat.

Our move meant that I had to start at yet another new school. That made five so far and I was still only 8-9. I settled in alright and seemed to make reasonable progress. At least I don’t remember getting into any trouble for being behind everyone else. I don’t have strong memories of that school, which was a short walk away near Wandsworth Common railway station. I do remember that in late Spring the country celebrated Empire Day*, a bit like the May Bank Holiday nowadays. It was traditional on that day to do the Maypole Dance.

* Empire Day was held on May 24th. It was instituted in the United Kingdom in 1904 by Lord Meath, and extended throughout the countries of the Commonwealth. This day was celebrated by lighting fireworks in back gardens or attending community bonfires. It gave the King’s people a chance to show their pride in being part of the British Empire. In 1958 Empire Day was renamed Commonwealth Day, in accordance with the new post-colonial relationship between the nations of the former empire.

Anyway this involved a tall pole, like a lamp post, and a lot of long coloured ribbons tied to the top. Each child had to take hold of a ribbon and hold it as far away from the pole as it would reach and all form a circle round the pole, making sure the ribbons started off untangled! Got that so far? Then you turned to face each other in pairs. Now comes the tricky bit! You had to skip lightly round the pole holding the ribbon up high with the hand nearest the pole and weave in and out of the person coming in the opposite direction. As you went on the outside of the first person they ducked under your arm holding the ribbon and then you ducked under the arm of the next one you met on their inside. Are you still with it? If it all went to plan the ribbons got shorter and shorter as you went round and round the pole and they formed a pretty coloured criss-cross pattern down the pole. That is IF IT ALL WENT TO PLAN! I can remember practicing this performance time after time and since we were just small children you might imagine we kept getting it wrong. We would go round the outside when we should have ducked under the inside. Someone would drop their ribbon. I don’t know how the teachers managed to keep their temper but I do remember we eventually got it right for the big day.

Back at the restaurant my Mum worked in the kitchen and was learning all sorts of new dishes from the chef who had stayed on when we took over the place. He was a lovely old man called Mr Bach. Dad looked after the accounts and such while Daisie Marshall did the waitressing. Harry Marshall was a lorry driver and went off to work. Sometimes if it was busy I was allowed to wait at the tables. Remember I was only eight but I used to get dressed up in my best shorts and white shirt with a small bow tie and take the orders and carefully carry the plates to the customer. I wasn’t able to carry three or four like you see proper waiters doing but I managed quite well. I think the customers thought it was cute for a little boy to be waiting and I would get some good tips! Ron and I also used to earn some pocket money preparing food in the kitchen. Not cooking of course but peeling potatoes and shelling peas. There were no frozen or ready prepared vegetables in those days!

By this time Ron was 14 and attending a special college to learn building trades and the like. The war was still raging and the air-raids continued although they seemed less common around us than they had been in Dockland. We did have a major scare on one occasion and were very lucky to escape serious injury. A parachute landmine had dropped on the Common just opposite us, but luckily had got caught up in the trees or something and had not exploded. We were all evacuated from the house while the bomb disposal team were called to tackle it which they did without it exploding and causing enormous damage to the buildings, including ours.

We didn’t have an Anderson shelter in our garden here; in fact we never had a garden, just a back yard that had been horse stables. When the raids got heavy we had to go along the road at the edge of the Common to a big public shelter. You could, sort of, reserve your bunk in these sometimes and there was a period when we spent regular nights trooping down the road to spend the night in the shelter.

Sometime in early summer 1944, something new happened in the air-raid department. A new German weapon appeared that was to cause quite a stir. This was like a small unmanned plane, complete with wings and jet rocket at the back to propel it. The problem was that it was a huge bomb! When these things started to arrive over the country the government thought they were a new super-fast fighter plane (a bit like a jet fighter which was to come much later) and the RAF sent up the usual fighters to engage them in air combat. Unfortunately they were fast and it was not easy to shoot them down. When they arrived over their target, mostly London at first, their rocket engines would cut out and they would just dive down to earth with an almighty explosion. They were called V1 rockets but were quickly nick-named Doodlebugs or Buzz bombs (because of the bee like droning noise they made). They brought a new and deadly threat to the people but amazingly people began to get used to them. Because they flew on a straight course and you could hear them coming it was easy to predict where they were likely to land. If you were not in their flight-path you were safe. If you were in their path you would listen to their engine as they approached and if it got very loud, meaning it was nearly overhead, you were also safe. You see, it was only after the engine cut out that the bomb would start to dive down to earth. You could even stand out to watch their progress. The real problem was if you saw one coming toward you and you saw its flame cut out BEFORE it reached you. Then you were in trouble! When they first started people would react the way they did in the old raids and run for shelter and sit listening for the crump of the explosions. After a while they realised that this was not like a raid by dozens of bombers dropping hundreds of bombs but a one off, albeit very big, bomb. Mind you, Jerry did send a lot of them one after the other, but you could still watch them. As a result a lot of people preferred to stay out and about but just keep their eyes and ears peeled for signs of one in their neighbourhood. That is what I preferred to do and, although Mum would worry about us, when we were out she knew that we would take shelter if danger came. Well for the most part that worked fine but I did have a close shave!

My mate and I were out one day near to Wandsworth Common Railway station when we heard the Doodlebug and were able to spot it in the sky. Unfortunately it was heading in our general direction so we were extra wary and just hoped it would pass over. We kept a close eye on it as we headed for home but then the noise stopped and we saw it tip down towards us. We both knew it was going to hit somewhere close by so we both ducked down behind a brick wall in front of a house and put our heads down and covered our ears. People were running for whatever shelter they could find. There was an almighty bang and we could feel the ground shake and the air rushed about us. There was dust in the air and when we poked our heads up above the wall we were amazed. Not far away across some open ground a whole railway wagon was perched on top of this big concrete shelter and rubble was all over the place. We took one look and ran for home as fast as we could. Mum breathed a huge sigh of relief because she knew it had been pretty close by and I was out there somewhere.

The aftermath of that particular bomb was to be pretty dramatic for me. First of all it had apparently landed on the railway close to Wandsworth Common station. It was also close to my school and caused a lot of damage which meant the school had to close down. No more school and an early start to the summer holidays! Secondly it was a bit too close for comfort as far as my Mum was concerned and I think she started to worry much more about my safety.

(I have since investigated this incident to check whether my memory was correct. Records show that a V1 did drop near Wandsworth Common Railway station at Ravenslea Road on the afternoon of 30th June and from my memory of where I hid behind a wall we were no more than 400 yards from it. What a lucky escape!!)

Shortly after that incident the Doodlebugs were joined by another weapon that was more deadly. The Germans had developed a more powerful and faster rocket. This one did not fly like a plane but like a modern day ballistic missile or space rocket. It also flew faster than the speed of sound which, unfortunately, meant that it hit and exploded BEFORE you heard it coming! They were called V2 rockets but people took them too seriously to come up with funny nick-names for them.

That summer, shortly before the V2 raids began, the whole family went on a holiday. We went to a small seaside village in Cumberland (now Cumbria) called Lowca, near Whitehaven. A strange choice looking back on it and I do not know to this day whether it really was chance or a crafty plan on the part of my parents and Uncle George. Be that as it may, we had a fun holiday up there wandering the hills far away from the rockets. It was great doing things together like going out in a fishing boat and just being together safely. Then we went to visit someone my Uncle George (Mum’s brother) knew. The family that owned the company where uncle worked were called Newton and they had a holiday flat in Keswick, not far from Lowca. A Mrs Mills looked after the flat and lived nearby. Why don’t we drop in to see them? They lived in a lovely little cottage and had a son about three years older than me called Ian. Well we did and Mum and Dad seemed to have deep conversations with Mr and Mrs Mills while I was sent out to play with Ian to get to know each other. I was never to return from that holiday to The Rendezvous!

As I say I never knew whether or not this was all a plot but what I was told was that the family were once again worried about the safety of being in London. Uncle George had suggested to my Mum that if she was so worried perhaps they should send me away again and this Mrs Mills might be willing to take me in as an evacuee. So I was left with the Mills family and Mum, Dad and Ron returned to London. I was to enter yet another new phase of my short life and one which holds bitter-sweet memories. There would be times when I was desperately unhappy there and others when I had wonderful adventures and fun. The lasting and really great outcome of it all was that I was to form a strong and lifelong friendship with Ian Mills as well as a loving relationship with his parents, Olive and Herbie/Mick until their deaths many years later.

Evacuation Again

Keswick

Firstly, a little about where I was to spend the next year of my life. Keswick is a lovely market town set in the north of the Lake District and nowadays it is a very popular and busy tourist destination. The Mills’ family lived just outside the main town in a small cottage; 2 Lydias Cottages, Brigham. It was tiny, with a small living room that you entered straight from the front door and a tiny scullery/kitchen off to the left. From that a small flight of stairs led up to two bedrooms. What about the toilet and bathroom you might ask? Well there was neither! The toilets were a row of six situated behind the other row of cottages that were off to the left about 20 yards away. Also round there was a wash house where the householders could do their weekly laundry. What a come-down after the Rendezvous where I had just got used to the luxury of indoor toilets and a bathroom.

I was to sleep in the smaller bedroom, sharing the bed with Ian whom I had only just met and who must have been wondering what his parents had landed him with. I can’t remember in detail what I felt in those early days after Mum and Dad went back to London except that I know I was very unhappy. In those first few weeks I kept trying to run away and I would climb out of the bedroom window but Ian usually either stopped me or brought me back. As I said, however, things were not all misery for I think children have a great capability to live for the moment and let other problems go away.

In those first few weeks Ian introduced me to the other children in the area and I soon joined in all their games and adventures. It was a lovely area around Brigham. Just across the road from Lydias cottages was the Twa Dogs Inn where Mr Mills would go for his drink, a ‘Black & Tan’. (You may not know what that is but it is a drink made up of half bitter beer and half Guinness stout). It was his favourite drink; not that he was the sort who would go off to the pub every night and get drunk. He could be quite severe with Ian and me although it was usually Ian that got the brunt of any scolding since he was a bit more than three years older than me. Mr Mills’ name was Herbert but was either called Herbie or Mick. In later years Ian was also often called Mick; I think it was a sort of family nick name. Anyway, Mr Mills worked in a mill, which was a coincidence wasn’t it! In fact it was a bobbin mill which you may never have heard of because nowadays they hardly exist except as historic monuments. (There is one at Finsthwaite near the bottom end of Windermere in the Lake District if you are ever up that way.) Bobbins were like giant cotton reels. They were produced very quickly on a wood turning lathe in a factory, or mill, where the machinery was all driven by the water power from the river. They were then sent to the cotton mills in Lancashire where the cotton thread would be wound round just like a small cotton reel that you use at home. These were then set up on the weaving machines in the mills to weave all the cotton fabrics. (Here ends the economic history lesson – sorry about that, I got carried away!) I have a strong memory of him returning home in the evening with his overalls covered in sawdust and he would stand in the room by the coal cupboard door and strip them off trying not to get sawdust everywhere. He often had a sack with him that contained bits of waste wood cuttings and even whole bobbins that were rejects because they had some fault or other. We even had a huge bobbin as a stool that sat by the fire at one end of the living room. I liked to go to see him at the mill to see all the machines working away and the lovely smell of wood being worked.

Anyway, back to the children and our games. Next to the Twa Dogs was a wooded copse where we would tear around with our swords or acorn guns or pea shooters and fight pretend battles. Hold on you might say, “What’s an acorn gun?” “The same as a potato gun only bigger”, says I. “Clever clogs, alright then, what’s a potato gun?”

Well, all you need is a length of tube of the right dimension, bigger for the acorn than the potato gun. We used a section of cane for ours but for the potato gun you can usually buy a small ready-made tube and plunger. For the acorn gun you need a tube about 1 foot long (30cm). You squeeze an acorn into each end and then use a stick to push the acorn from one end towards the other. If you push hard enough the other acorn will fire out of the tube and travel a good distance. It all works by the power of compressed air. Nowadays you can buy ready-made plastic toys that use ping-pong balls or such like, but at that time we had to make our own toys. (Here ends the science lecture – sorry I got carried away yet again!!) Swords, bows & arrows and such were cut from ash and willow trees and most boys would have a pen-knife as a basic piece of equipment for such tasks.

Because I was under the wing of Ian I was quickly accepted by the other children although I still had to prove myself. Luckily I was good at sports and I could run and climb with the best of them. In fact my climbing prowess was highly regarded and I was often the one to climb into difficult areas when we went bird-nesting. I remember climbing along the girders of the railway bridge over the beck to find a nest. That’s another thing that is discouraged now since it is important to preserve the bird life but in those days most boys in the countryside would have an egg collection. We did take care about preservation even then, though, because it wasn’t done to take more than one egg from a nest (or perhaps two if it was a big clutch). When you got an egg the next problem was how to keep it for your collection. If you just put it away it would go bad and smell the place out if it ever broke. So you had to ‘blow’ the egg. This involved carefully piercing a small hole in each end and blowing at one end to push the yolk and white out at the other. This was very tricky and often ended with a broken egg. It is all banned nowadays, but we had great times hunting for the nests all over the place. You can still do the same today, but take binoculars and camera instead and just look and observe the birds.

Just down the road from the house was Town Field, a park and open play space with lots of room for football and cricket. (If you explore street view on Googlemap you may find Town Field with the beck, and Twa Dogs inn. The copse is now full of houses in Latrigg Close.) Flowing alongside this was Greta Beck, a fast flowing mountain river which had lovely crystal clear water. In one corner the field dropped down to the riverside and formed a small shingle beach. The beck at that point had just passed some rocky section and formed a wide calm pool. That is where we were able to go swimming although the water was freezing cold. At that time I couldn’t swim but could wade in quite safely and splash about.

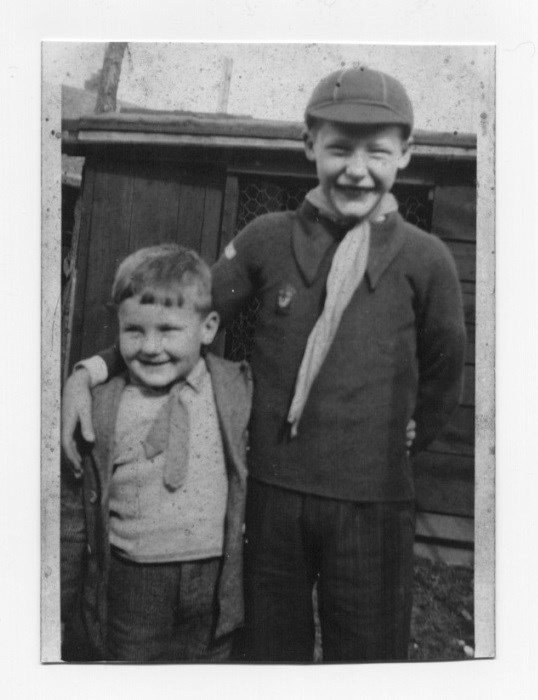

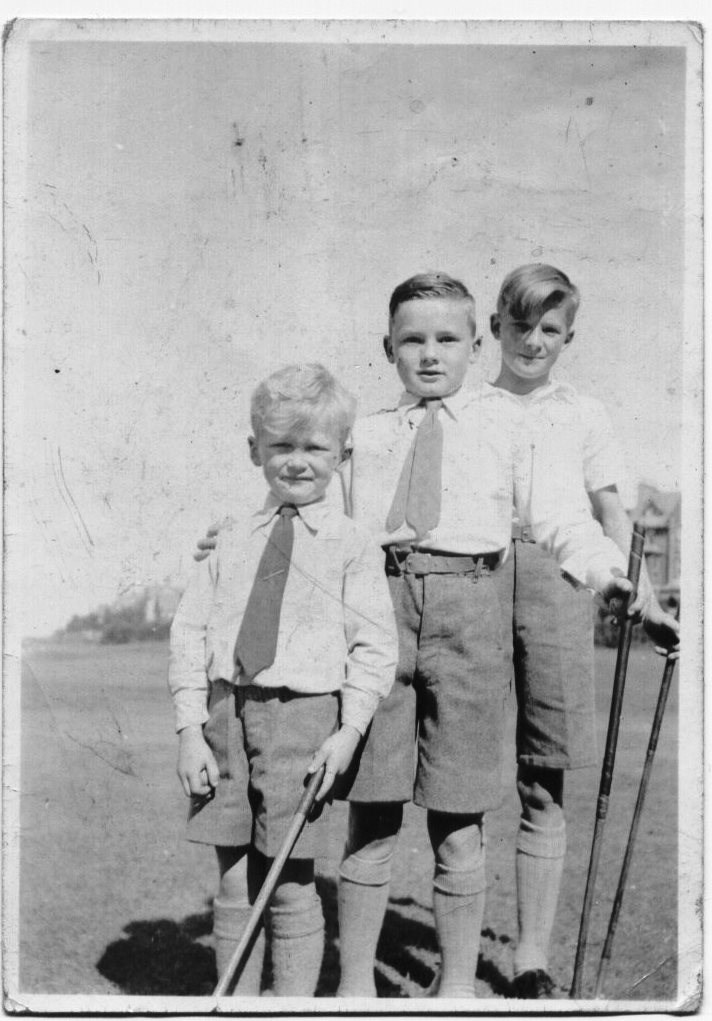

All those memories are of good times but, as I said, I had some miserable times too. You remember I talked about my wetting the bed when I was in Bridgwater? Well I have no recollection of the same problem when we were back in London but after I was left in Keswick it started again. This time the difference was that Mrs Mills was much kinder and poor Ian had to suffer the problem of waking up in bed with a soaking sheet and, often, his own pyjamas wet from my weeing! I would get very upset and we tried all sorts to solve it but it persisted. What was worse was that I started wetting and soiling my pants during the day. I was so ashamed, yet for some reason I found myself unable to stop. Sometimes when I was out and about I would duck behind a bush or something but that was not always possible. I attended the primary school in Brigham just along the road from the cottage and we had a very severe teacher. I was afraid of her a bit and I remember I would be too timid to put my hand up to be excused to go to the toilet and would sit at my desk and wee my pants. I know that sounds horrid now, but I assure you it wasn’t fun for me at the time. I remember I had a pair of thick brown corduroy shorts and Mrs Mills was always washing them out. By the way, in those days all little boys wore shorts until they were about 13 or 14. Not sports shorts, like football or tennis shorts, but proper tailored short trousers that came to the knees. We had long socks that came to just below the knee and were kept up by elastic garters round the top, although they would often fall down in a scruffy bundle around the ankles. In the picture below we are very smart though. This was taken in July 1944 shortly after I arrived in Keswick and shows me between Ian and my cousin Stuart.

In London I wore ordinary shoes but in some places in the North of England it was common to wear clogs. Not the sort you see little Dutch boys wearing, all carved out of wood, although these did have a wooden sole. On top of the wooden sole was a boot shaped leather top with leather laces to tie them up. Underneath a metal strip, like a horse shoe, was nailed for the sole and the heel.